Encefalopatía Espongiforme Bovina

También conocida como: EEB - Enfermedad de las Vacas Locas

Introducción

La EEB fue reconocida por primera vez en Reino Unido en 1986 tras una gran epidemia en la que se vieron envueltos más de 100.000 animales enfermos. Con la excepción de Francia y Portugal, el número de animales infectados en otros países se ha mantenido bajo. La enfermedad está ahora distribuida por todo el mundo y existen datos de casos producidos en Europa, Asia, Oriente Medio y América del Norte.

La encefalopatía espongiforme bovina (EEB) es una enfermedad nerviosa progresiva, mortal y no febril que afecta a los bovinos adultos. Pertenece a un grupo de enfermedades llamadas encefalopatías espongiformes transmisibles (EET), también conocidas como enfermedades priónicas. Puede ser causada por una enfermedad genética o infecciosa. Se produce cuando la conformación de los priones naturales PrP se transforma en la isoforma patógena PrP sc y produce degeneración espongiosa del cerebro. En las enfermedades priónicas genéticas, este hecho puede ser causado por una mutación somática en el gen PrP c. En la encefalopatía espongiforme bovina infecciosa, la exposición a un prion PrP sc extraño puede iniciar este cambio de conformación, lo que da lugar a una cascada progresiva de cambios en la conformación de los priones naturales PrP c a PrP sc [1].

El ganado se infectó por primera vez con los priones anormales a través de la alimentación con piensos que contenían proteínas derivadas de ingredientes tales como harina de carne y huesos (HCH) procedentes de rumiantes. Se cree que los cambios en el proceso de fabricación de HCH aumentaba la supervivencia de materiales similares a scrapie (priones) de las canales de ovino infectadas y el uso de despojos infectados de la misma especie bovina pudo conducir a la propagación de la EEB a través de la HCH infectada.

No existen datos para afirmar la posibilidad de transmisión horizontal de la EEB en circunstancias naturales, pero hay datos que apoyan la transmisión vertical [2], [3], [4], [5], [6]. La EEB es una enfermedad de declaración obligatoria y a diferencia del scrapie se considera zoonosis.

Características

La enfermedad tiene un período de incubación muy largo (aproximadamente 4 - 5 años) y afecta principalmente a animales de 4-6 años de edad. La enfermedad ocasiona signos neurológicos que pueden durar varios meses y cuyo desenlace es la muerte. No hay predisposición de raza o sexo, sin embargo, la incidencia de la EEB en las vacas lecheras es mucho mayor que en las vacas de carne, probablemente este hecho esté relacionado con un mayor uso de raciones de concentrados que contienen harinas.

Las encefalopatías espongiformes también pueden presentarse en nuevas especies como el kudu mayor, Nyala, onynx árabe, oryx de cuernos en cimitarra, eland, Gemsbok, bisontes, Ankole, tigre, guepardo, ocelote, puma y gatos domésticos, durante la década de 1990 [7], [8] , [1] y en 2005 una cabra fue confirmada como positiva para la EEB en Francia. Hasta la fecha no hay evidencia científica de que la infección experimental vía oral de EEB sea un problema para cerdos y aves de corral alimentados con material de riesgo de ganado afectado por EEB.

Signos Clínicos

El primer signo suele ser separación de la manada y la reticencia a moverse en la sala de ordeño y los animales pueden reaccionar pateando de forma vigorosa.

Los afectados por EEB muestran progresivos cambios neurológicos y de comportamiento, anormalidades en la postura y el movimiento, postración, cambios en la sensibilidad y el temperamento y agresividad. Los signos clínicos más destacados son nerviosismo, temblores, caídas, hiperestesia al sonido y tacto, debilidad progresiva y ataxia de los miembros posteriores - y la agalaxia o disminución del rendimiento y de la producción.

Otros signos clínicos incluyen anorexia, pérdida de peso, bruxismo, ptialismo, trismo, prurito, córnea áspera y opaca, signos oftálmicos como la ceguera, lagrimeo, ptosis palpebral y prolapso del tercer párpado.

Diagnóstico

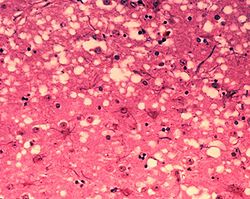

A preliminary diagnosis can be made on observation of the above clinical signs. The disease is characterized by accumulation of prion protein in the medulla oblongata (obex) region of the brain, as well as other tissues (lymph nodes, spleen, tonsils, etc) and can be confirmed on post mortem by the presence of the following histological changes in the brain: bilateral symmetrical vacuolation and immunohistochemical demonstration of the accumulation of the disease specific PrPsc in the grey matter of the brain, gliosis, hypertrophy of astrocytes, neuronal degeneration and cerebral amyloidosis.

The absence of detectable immune responses in BSE precludes any serological test for the detection of antibodies.

For surveillance, a number of rapid tests on brain samples have been developed and approved by the European Union. These include the Western Blot test (detection of PrPres), Luminescence immunoassay (detection of disease specific prion proteins), and Chemiluminescent ELISA test.

Differential diagnosis: hypomagnesemia, nervous acetonemia, lead poisoning, intracranial tumours, and infectious diseases such as rabies, listeriosis , Aujeszky’s disease and cerebro-cortical-necrosis (CCN).

Tratamiento

Actualmente no existe una vacuna o protocolo de tratamiento para esta enfermedad.

Control

BSE is extremely difficult to control due to its long incubation period and the fact that the altered prions are extremely resistant to heat and chemicals. Stringent preventive measures are in place to stop the spread of the disease, prevent cattle and human exposure and to eradicate BSE from the animal population.

The most important of these measures has been the feed ban issued in 1988, prohibiting the feeding of ruminant derived meat and bone meal (MBM) to ruminants [9] and the adoption of the ban by the EU in 1994.

Post mortem testing schemes and culling of infected cohort animals have also helped to reduce the spread of BSE. So far they have resulted in a significant decrease in the number of BSE cases in the UK and other affected countries. Currently, the number of cases in the UK is decreasing.

For countries that are BSE free, preventative measures are ruminant to ruminant feed ban, import controls and surveillance.

To reduce the risk to humans developing variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (vCJD) all visible nervous and lymphatic tissue that are classified as specified risk materials (SRM) are removed during the processing of cattle as well as the removal of any suspect animals from the human food chain.

Specified risk material of cattle includes: brain, eyes (retina), trigeminal ganglia, the spinal cord, the dorsal root ganglia, mesentery, intestines (duodenum to rectum) and tonsils.

SRM in sheep and goats include: spleen, ileum, spinal cord, brain, eyes and tonsils.

In 1996, cattle over the age of 30 months were eliminated from the food chain within the UK under the ‘over thirty months scheme’ (OTMS). This ban has now been lifted and it is now compulsory to test all cattle over the age of 48months for BSE.

Refereneces

- ↑ 1,0 1,1 Prusiner, S.B. (1997) Prion diseases. In: Viral pathogenesis. Nathanson, et al., eds. Philadelphia, USA: Lippin-Cott-Raven Publishers, 871-911.

- ↑ Wilesmith, J.W., Ryan, J.B.M. (1997) Absence of BSE in the offspring of pedigree suckler cows affected by BSE in Great Britain. Veterinary Record, 141(10):250-251; 5 ref.

- ↑ Donnelly ,C.A. (1998) Maternal transmission of BSE: interpretation of the data on the offspring of BSE-affected pedigree suckler cows. Veterinary Record, 142(21):579-580; 9 ref..

- ↑ Fatzer, R., Ehrensperger, F., Heim, D., Schmidt, J., Schmitt, A., Braun, U., Vandevelde, M. (1998) Investigation of 182 offspring of cows with bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in Switzerland. Part 2. Epidemiological and neuropathological results. Schweizer Archiv für Tierheilkunde, 140(6):250-254; 14 ref.

- ↑ Schreuder BEC (1998) Epidemiological aspects of scrapie and BSE including a risk assessment study. ISBN 90-393-1636-8. Thesis University of Utrecht

- ↑ OIE (2000) Bovine spongiform encephalopathy. In: OIE Manual of Standards for diagnostic tests and vaccines. Office International des Epizooties (edition 4), 457-460.

- ↑ Benbow, G.M. (1990) Zoo animal BSE. Vet. Rec. 126:441.

- ↑ Collinge, J. (2001) Prion diseases of humans and animals: their causes and molecular basis. Ann. Rev. Neurosci. 24:519-550.

- ↑ Hoinville, L.J. (1994) Decline in the incidence of BSE in cattle born after the introduction of the 'feed ban'. Veterinary Record, 134(11):274-275; 12 ref.

| Encefalopatía Espongiforme Bovina Entorno de Enseñanza Virtual | |

|---|---|

Comprobar tus conocimientos utilizando preguntas de tipo Flashcard |

BSE in Cattle Flashcards |

|

Este artículo fue originalmente de The Animal Health & Production Compendium (AHPC) publicado en el web por CABI. Hoja(s) de datos utilizados: bovine spongiform encephalopathy el 30 May 2011 |

Links

List of Member Countries' BSE risk status from the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE)

| Este artículo ha sido revisado por pares, pero aún no ha sido evaluado por un experto. |