Casco - Anatomía & Fisiología

Introducción

La pezuña se define, desde un punto de vista fisiológico, como la piel modificada que cubre el órgano digital, y las estructuras relacionadas. Aporta protección al órgano digital y se forma por queratinización de la capa epitelial, y modificación de la dermis adyacente. La queratina de la epidermis, se engrosa y se cornifica, formando el corion, que cubre el casco y es muy resistente a daño mecánico.

El origen del casco o pezuña es como forma de protección de la falange distal, y se debe a modificaciones locales de la epidermis, dermis y capas subcutáneas. Hay una gran variación interespecífica en la forma de las diferentes pezuñas de nuestras especies domésticas. En algunas especies se ha especializado en escavar o en usarse como defensa, mientras que en otras se ha adaptado a mejorar la carrera y la locomoción. También actúa como amortiguador de golpes, reduciendo el impacto de la falange distal. También se piensa que la naturaleza elástica del tejido facilita el retorno de la sangre al corazón.

Las Cinco Regiones de la Pezuña o Casco

Región Parietal (Pared)

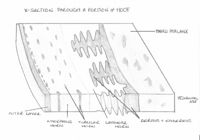

La pared del estuche córneo es el elemento visible externamente. Es más ancha en la cara dorsal y más fina lateral y medialmente (alrededor de las cuartillas). En la mayoría de las especies domésticas tiene un grosor aproximado de 5-10 mm, y se divide en tres capas. Una capa externa de poco grosor pero densa, que es brillante y evita la evaporación y deshidratación de las otras capas. Una capa intermedia, que representa la estructura principal del corion, y está formada por material córneo amorfo y túbulos de material córneo. Por último, la capa interna laminar, donde encontramos láminas interdigitales de material córneo y láminas dérmicas que anclan el casco a la falange distal. La unión entre el corion y la dermis, es móvil y permite que la pared se deslice en dirección distal, para realizar el contacto con el suelo.

Región Perióplica (Limbo)

Es una pequeña capa de tejido blando, que se encuentra sobre la superficie proximal de la pared. El limbo representa la unión entre la pared y la piel, y es responsable de la producción de la capa externa de la pared. Se extiende alrededor del eje proximal de la pared y, en équidos, cubre el bulbo y parte de la ranilla. En rumiantes forma parte de la unión entre ambas pezuñas y el pie.

Región Coronal (Corona)

Se encarga de producir la pared de la pezuña, que crece en dirección distal desde la dermis coronal. Está repleta de papilas que se proyectan hacia el suelo en dirección del crecimiento. La epidermis que las cubre produce túbulos de material córneo en un entramado con material córneo amorfo intertubular, formado por los espacios entre la dermis coronal. Esto garantiza un casco fuerte y resistente.

La pigmentación de la pezuña o casco, se lleva a cabo por melanocitos, presentes en la epidermis coronal. Cualquier pigmentación será más pronunciada en la parte externa, donde encontramos más melanocitos. Podemos hallar una zona libre de pigmentación llamada la línea blanca en la suela, muy importante en caballos como marca para herrarlo correctamente.

Región Solear (Suela)

La suela representa la parte del pie que contacta con la suela, y su composición difiere entre especies. La queratina que encontramos en la suela se forma a partir de la epidermis que se encuentra bajo la tercera falange, y puede crecer hasta un grosor de 10mm en las especies domésticas. Aunque se desgasta más fácilmente que la queratina que encontramos en la región dorsal. En équidos la suela tiene una ranilla central, mientras que en rumiantes y en porcino encontramos un bulbo en la suela.

Ranilla y Bulbo

La cuña córnea o ranilla de los équidos, se forma a partir de queratina de la misma manera que la suela, y asimismo la queratina es más flexible que la que encontramos en el estuche córneo. La ranilla asegura que la pared del casco se fuerce hacia afuera cuando el animal apoya su peso en ella, asegurando un buen apoyo y una buena circulación hacia el corazón.

La cuña de rumiantes y porcino permite el contacto caudalmente con el suelo, y mejora el apoyo y el soporte del peso del animal. Se inserta en el borde central de la suela, con forma de V, y está formada por material flexible y relativamente blando, de gran grosor.

Estructura y Función

Casco de Équidos

As outlined above, the equine hoof can be divided into three topographical regions; the wall, the frog and the sole. The wall forms the medial, lateral and dorsal aspect of the hoof and it can be further divided into the toe, quarters and heels. At the heel the walls reflect back on themselves at a point called the angles and in doing so forms the bars. The bars, although moving cranially, gradually fade along the edge of the frog and never actually meet. The frog sits between the bars and has an apex facing distally, with 2 crura flanking a central sulcus. Between the crus and bar of each half of the sole lies the collateral sulcus. Opposite the apex, the frog expands forming the bulbs of the heel. The sole is the area distal to the bars and apex of the frog enclosed by the hoof wall. The area where the bars and wall enclose it is known as the angle of the sole.

The dermis of the distal phalanx is arranged in hundreds of leaves or laminae, each of which has microscopic secondary laminae. The coronary region has a germinative layer associated with papillae that is responsible for producing the horn tubules that make up the hoof wall. This wall glides distally at a rate of 5-6mm a month and by forming epidermal laminae itself it interdigitates with the underlying dermal laminae. Neither of these laminae are pigmented so when the epidermal laminae appear on the solar surface, a non-pigmented region known as the white line appears. The white line is used as important landmark in farriery as structures central to the line will be dermal and so vascular and sensitive.

The dermis in the frog is also arranged in papillae and produces incompletely keratinised flexuous horn tubules resulting in a soft, elastic horn. The hypodermis of the region of the frog forms the digital cushion. This lies between the ungual cartilages and is collagenous, elastic tissue infiltrated by adipose tissue. At the bulbs of the heel, it is subcutaneous and is soft and loose in texture. The sole area also has papillae that produces superficially flakey horn. The coronary part of the wall is surrounded by a bony prominence called the periople. This soft, lightly coloured area is restricted to this proximal area and is produced by the germative layer covering the papillae. The rest of the hoof is covered by the tectorial layer, this is a very thin layer of horn that is covered distally by the growth of the horn.

A well-trimmed foot should weight bear on its walls, bars and frog. This occurs as the weight applied to the distal phalanx is then transferred across the interdigitating laminae to the hoof wall. Thus an injury resulting in damage to the laminae is of extreme importance to the horse.

See equine phalages for further detail.

Ruminant Hoof

The ruminant hoof, although resembling the equine hoof in some characteristics, differs from the equine hoof in several ways. In the ruminant hoof there are two separate main digits and the wall of the hoof is bent to form a border. Also the bulb of the heel covers the entire caudal surface of the hoof and most of the plantar surface, leaving only a small area of sole visible. In ruminants the interdigitating lamellae are smaller and less well developed than in equids.

The hooves of the main digits curve medially towards each other. The lateral digit carries more weight than the medial digit, and is larger. On the abaxial wall, the distal border makes contact with the ground along its entire length, whereas, on the axial wall, only does so toward the toe. The thickness of the wall increases towards the apex and the plantar surface. The horn of the hoof generally grows at a rate of 5 mm per month, and in cattle allowed to move freely, growth should equal wear. In intensively kept cattle, growth exceeds wear, and foot trimming is required to maintain optimal shape and angle. The optimal angle of the toe from the ground is 50 degrees. Where horn overgrowth occurs, the coffin joint is gradually overextended and the deep flexor tendon tensed. This results in greater weight being placed over the caudal part of the hoof and can cause pain and lameness.

Dewclaws are present in most ruminants but do not make contact with the ground. They consist of wall and bulb and have no practical importance.

See the bovine lower limb for further detail.

Porcine Hoof

The hooves of pigs are principally similar to those of ruminants, however the wall is straight, not bent medially at the toe, and they have a soft bulb that is well distanced from the wall and sole. The hooves of the accessory digits are of the same structure as the principal digits, but only bear weight on soft ground.

Hoof trimming in pigs is rarely required due to the short lifespan of the farmed pig.

| Este artículo ha sido revisado por pares, pero aún no ha sido evaluado por un experto. |

Este artículo ha sido traducido de Inglés por 'Fanny Olsson' - 16.09.2011. |